This is the biography of James Toone of Virginia. Born in England, he arrived in Virginia in 1651 and is the first of our TUNE surname in the United States. This historical biography is for all descendants of James Toone (c. 1625-1677) and all those carrying the Tune surname whose frequency is most predominant in the southern US. This biography is also for all of our numerous collateral families without whom our legacy could not have continued.

The story of James Toone of Virginia and England is currently a work in progress. Read on and subscribe at the end of this post if you would like to receive updates as I continue adding to the narrative of his life, indeed all of our lives as descendants of the TUNE surname in the US.

style=”display:block” data-ad-client=”ca-pub-4223521512758623″ data-ad-slot=”7477297085″ data-ad-format=”auto” data-full-width-responsive=”true”>- Life in 17th Century England

- English Population Boom

- The Toones of Leicestershire, England

- Cavaliers and the English Civil War

- Transportation to Virginia

- Life in Virginia in the 1650s

- The Indentured Servant

- Land Patent Explosion

- James Toone of Virginia and the Planter Class

- James Toone of Virginia Establishes Himself

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Sources

Life in 17th Century England

Life in England in the early 1600s was exceedingly difficult. The romantic medieval life we normally associate with traditional English culture had broken down and war had broken out by 1641 that would last until the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Death had perniciously gripped the country in the form of plagues and scourges, most notably during early 1300s, the 1560s, and the 1660s.

All of that not withstanding, England was right in the middle of a tremendous population boom which would swell to over 5 million people by the time James Toone decided on leaving England for the American colonies around 1650.

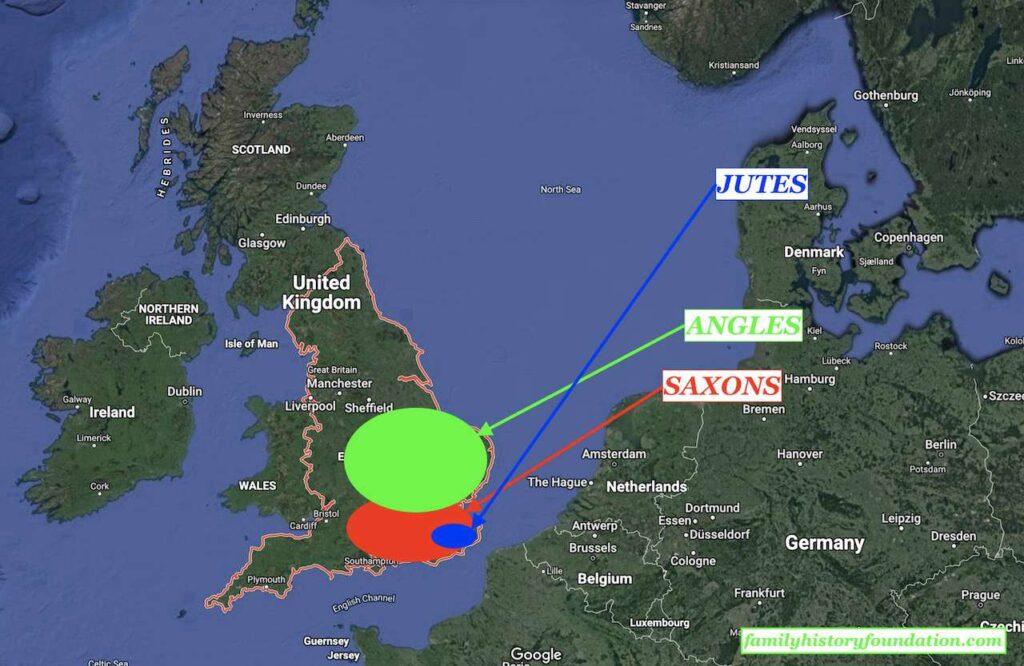

James must have grown up in a village not more than 100 miles away from London. As 80-90% of the population of indentured servants sailed from London in the first four decades of the 1600s, it is most likely that he was raised in the Home Counties1 or out in one of the surrounding shires west or north of Buckinghamshire. It was less likely that he was from East Anglia as they comprised the majority of emigrants to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and our James planted his roots in Virginia.

Life through the eyes of young James Toone must have been amazing as he lived intertwined in a socio-cultural patchwork that has been eloquently described as a “motif of plenty and want” (Horn 1994: 48). In the early 1600s, in an era when 4/5ths of the population of England lived in the countryside, it must have been a time of wonderment to be listening to stories of family hardship and economic deprivation from the multitudes of sons who had left their families and their home villages to seek out a different life in a port city such as London. As they literally poured out of their native shires,2 they must have encountered one another on their journeys crisscrossing the English landscape in search of economic promise.

English Population Boom

The population boom and economic downturns in the textile industries in the 17th century had placed such enormous pressures on village life that the traditional manorial agrarian system simply could not sustain the thousands of people living in their respective hamlets, which only a few generations earlier supported a few hundred (Fischer 1991). Abrupt changes in technology and the feudal class system also precipitated the collapse of what is referred to by medieval scholars as the “open field village” (Gies 1991: 205).

The death-knell to the future of many an English son like James Toone must have been the law of primogeniture. As only the eldest male could inherit and sisters naturally married off to join their husband’s family, younger children like James3 were often left out in the cold to fend for themselves.

James Toone was a courageous, tenacious, and clever fellow to have set out with all the odds of the world against him and eventually find success overseas. However, it is a bit romanticized to think that James had some sort of epiphanous vision of life in the American colonies which one day prompted his exodus from his home shire and farm in England. That would be editorializing. What most likely happened adds another level of courageousness and respect to an ancestor who is already superhuman in my eyes – and while this biography might have occasion to be labeled a hagiography by traditional historians, it honors an ancestor of whom I am extremely proud.

The Toones of Leicestershire, England

The Toones are an ancient family seated in the county of Leicestershire, England, primarily in Belton, Osgathorpe, and Rotherby. The history of the Toone surname in this area goes back to at least the 14th century via evidence corroborated by numerous parish records housed in the National Archives UK.

According to H. P. Guppy’s Homes of Family Names in Great Britain, “Toone was the name of an ancient Leicestershire family of Belton and Osgathorpe that branched off at the end of the 16th century from the Toones of Burton-on-Trent, in the neighbouring county of Stafford” (Guppy 1890: 267).

One thing is for certain, between 1600 and 1660 in Leicestershire, neighboring Staffordshire, Worcestershire, and London, there were a plethora of Toones! The historical records are full of wills, lawsuits, deeds, collections, and legal battles due to the position of the family as merchants. They seemed to be a fairly influential bunch.

During my research on the Toones of Leicestershire during this same time period, I came across historical records describing a surprising array of occupations in which the Toones were engaged. Some of these are very interesting: haberdasher, land owners, butcher, clothier, gentleman, apothecary, yeoman, clothworker, vintner!

In The Visitation of the County of Leicester in the Year 1619, it lists the “Toones of Belton” as being a prominent family on page ix. In that year the Clarenceux King of Arms, who was an officer for the College of Arms, set about visiting Leicestershire to record pedigrees and grant arms to those warranting such a rise in station.

In The History and Antiquities of Leicestershire, it recognizes “the pedigree of TOONE of Belton and Osgathorpe” (Nichols 1815: 650). It also provides a heraldic description of the arms granted to a “William Toone, of Osgathorpe, descended from the Toones of Burton on Trent” as being “Arms: argent, a maunch Gules. Crest, a dexter-hand and arm couped, grasping a snake Proper” (ibid.).

However, just because arms were granted to this singular William Toone (sometime in the late 1500s I’m presuming, based on the death of his grandson Hamlett Toone in 1638), that does not mean that all of his descendants can carry these arms. Arms are granted to individuals, not families.

The arms granted above are attached to the prolific line of Hamlett Toone. As for the story of James Toone of Virginia, I am yet uncertain as to how our James fits into this particular Toone family line. So the story continues!

Cavaliers and the English Civil War

“According to this design, he contrived a severe act of Parliament, whereby he prohibited the plantations from receiving or exporting any European commodities, but what should be carried to them by Englishmen, and in English built ships”

~~ Oliver Cromwell (Beverley 1855: 51).

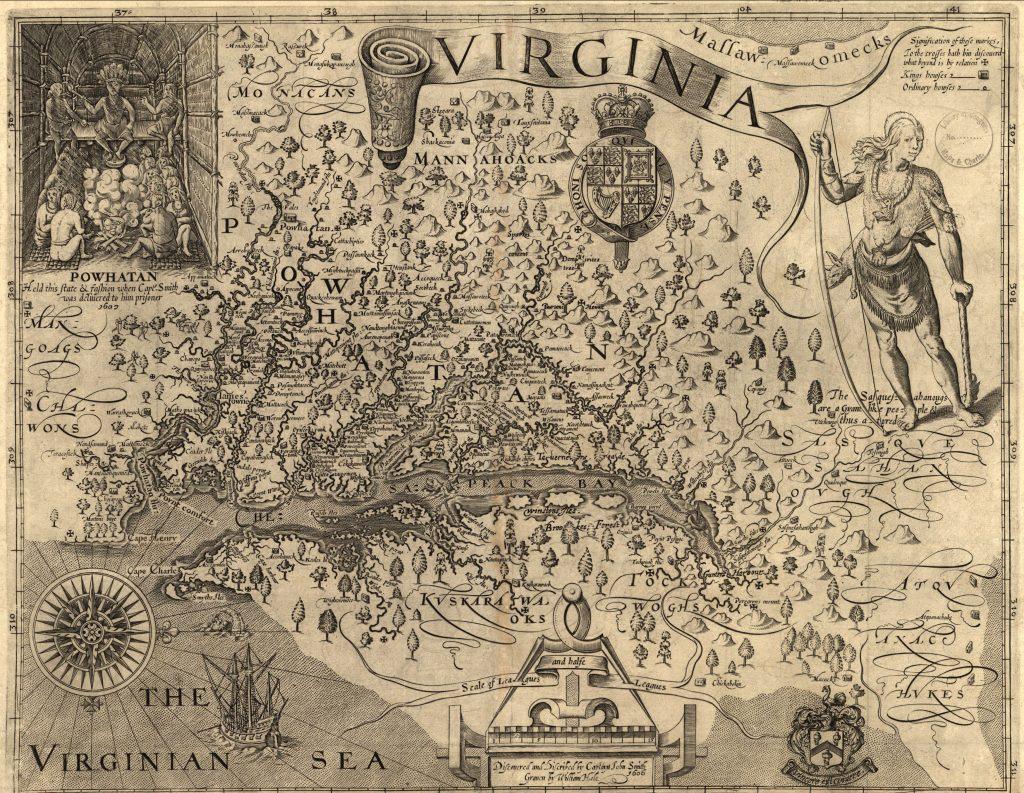

The fates, fortunes, and families of the Virginia Colony were inexorably tied to England. In 1651, the very first year we find James Toone’s name documented in Virginia, England was at the apex of the bloodiest portion of a Civil War that would indelibly alter the foundations of English government through the creation of a Parliamentary system under Oliver Cromwell. These events would, therefore, also affect the legal, political, and social realities of her colonies in the Americas as well as the Caribbean.

It is worth a moment to pause and reflect on the state of the political connection between Virginia and England during the late 17th century.

This Parliamentary system under Oliver Cromwell was responsible for an incessant coup beginning in 1642 that culminated in the ruthless beheading of Charles I in 1649. Charles I was the successor to James I for whom the famous Jamestown was named. Immediately after Charles I was publicly executed, his son Charles II was exiled and the insurgent government known as the Protectorate was established which controlled England from 1649 until 1660.12 This period, formally known as the Interregnum, ended with the restoration of Charles II and the creation of his Cavalier Parliament that lasted until 1685.

The word ‘Cavalier’ should not be unfamiliar to any Virginia historian or genealogist. In Virginia as in England, according to the parlance of the times, people were dichotomously either Roundheads (supporters of Cromwell’s Parliament) or Cavaliers, those considered loyal to Charles I and II and who were also considered Royalists. One of the most prominent citizens in Virginia during this time sporting the appellation Cavalier was Sir William Berkeley, governor of the Virginia Colony from 1641 to 1652 and then again from 1660 to 1677 – basically spanning the time that James Toone arrived in Virginia, created his legacy, and was ultimately laid to rest in the “freshes” of Farhnam Creek.

As Sir William Berkeley was appointed by Charles I in 164113, he was also forced to “retire” in 1652 (which began the 8-year period between his two stints as governor) when a commission was sent to Virginia to demand the surrender of the colony to the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Knowing that a revolution was brewing in England, Sir William Berkeley becomes instrumental in the peopling of the Virginia Colony in that he actively sought out and encouraged those Cavaliers in England and offered them refuge in Virginia. In fact, from 1649 on there was a “great exodus” of Cavaliers from England to Virginia where they fled for safety at the behest of our governor Berkeley. Our James Toone, conveniently enough, arrives exactly during this time period! What might this tell us about him?

Transportation to Virginia

His decision to leave England for the American Colonies had to have come while he was living in London4 sometime in the late 1640s. The conditions in London at that time were so harsh that taking his chance in America must have seemed “tempting” (Horn 1994: 48).

Although many facets of James Toone’s life in England will remain a mystery, we may surmise that he was most likely not of the gentry class. According to Nell Nugent in Cavaliers and Pioneers (1934: 221) James Toone in 1651 is listed among passengers whose transportation was paid for by a John King.5 Our James Toone is listed on that registry as James Town.6

As established families usually traveled together, James’ name alongside three other people who do not appear to be related, stands in sharp contrast to someone of ready financial means and the ability to pay for their own transportation costs. In addition, “the lure of cheap land” as a singular motivation to relocate was often an indication of someone from a more humble background (Walsh 2010: 41).

According to James Horn (1994) a middle class person in England in the mid 17th century had a net worth of £50-99. On the other end of the spectrum, receiving “alms” and “parish relief” was becoming increasingly widespread as people went on the dole much like in modern society (1994). Although James had left his family behind in his native county, he kept with him the wisdom and love imparted to him during his upbringing, a set of values that gave him the fortitude to stand on his own and establish his own family. There exists the possibility that he may have been economically destitute but he was rich in morals, love, and strength of will!

James left his home shire on his own, paid for (or repaid) his emigration on his own, all through his own hard work, resourcefulness and steadfast moral character. It actually wasn’t such a bad deal for a young, virulent Englishman at the time; the cost of transportation was about £6 and the terms of service were usually between four and five years7 in the first half of the 17th century.

All that being said, there is also the possibility that James Toone of Virginia may have had some financial backing from his merchant Toone connections and that he established himself in Virginia as such! Future research will eventually bear this out.

One thing is for certain, James also had great timing on his side as he entered the Virginia Colony in 1651, right at the beginning of a very prosperous age that began in the late 1640s and lasted through to the late 1660s. Lorena Walsh (2010: 131) describes this time as “the Golden Age of the small planter in the colonial Chesapeake.”

Life in Virginia in the 1650s

The original Jamestown settlement had lived through horrific circumstances from its original founding in 1607 until the 1630s when life finally started to balance out. On the other side of the coin, by the 1670s life in the Chesapeake “had changed beyond recognition” in relationship to the 1630s (Horn 1994: 123) and by the time the 1680s rolled around a severe economic depression had hit that would last until around 1715. Those were truly trying times; however, James Toone arrived at just the right period in Virginia’s history that lent maximum effect to the establishing of his family and fortunes.

In order to understand James Toone of Virginia’s life and circumstances upon landing on the shores of the Chesapeake in 1651, certain statistics need to come to light. First and foremost was that the Chesapeake Bay at that time was not a healthy environment – this is quite ironic as James landed during an economic boom. The mortality rate was about 1:3, up to 40% in the Tidewater region.

The ratio of men to women was 3:1 and over 25% of men died intestate in the last half of the 1600s.8 So many people died that the population of Virginia wasn’t even self-sustaining until the latter part of the 17th century! One of the major reasons cited is that the tobacco economy of the region demanded a continual influx of labor to support production and offset human “wastage” (Horn 1994: 137; Fischer 1991).

In the 1650s through the 1670s indentured servants formed almost 50% of the base population. When looking at immigration statistics from that same era: “more than 75% came as indentured servants” to Virginia primarily from Bristol, England (Fischer 1991: 227). Dabney tells us that indentured servants “were often people of good standing in England” (Dabney 1971: 34) and that many rose to positions of power after their terms of service, although some scholars have challenged the paucity of these population percentages.9

It was the youngest segment of society where someone like James would have finished his service in his early 20s, as was typical for most indentures at the time (Horn 1994). Below are population statistics for the Chesapeake during the time period covering 1607 – 1700 (Fischer: 136):

| Year: | Total Population: |

| 1607 | 105 |

| 1620 | 900 |

| 1640 | 8,000 |

| 1660 | 25,000 |

| 1680 | 60,000 |

| 1700 | 85,000 |

| Decade(s): | Pop. increase per decade: |

| 1630s-1640s | ~ 8-9,000/decade |

| 1650-1680 | ~ 16-20,000/decade |

If James Toone was an indentured servant we do not know who he worked for when he arrived in Virginia, we also do not know where he first lived as a consequence. What we do know is that he acquired his first land patent in 1663, which was a joint land conveyance of 656 acres to both James Toone and a Luke Billington – 328 acres each along the Rappahannock River.

The Indentured Servant

One of the most persistent and prevalent features of Colonial Virginia is the indentured servant. These were a class of people who could not afford to pay for their passage from England to the Virginia Colony and therefore had to repay that cost with service to a family, usually in the form of farm labor.

The word indenture refers to a specific type of contract whereby the terms of a fiduciary agreement is satisfied via labor and/or apprenticeship. The word servant refers to the fact that the indentured party was not on equal footing economically (and often not socially) with the party holding the contract.

The origin of the indentured servant in Virginia is inexorably attached to the headright system which was established all the way back in 1616. It was at the same time an investment strategy and a social experiment.

“Settlers who had arrived before spring 1616, who were termed ‘ancient planters,’ were to receive one hundred acres for their own adventure and if they were investors another one hundred acres for every share purchased. Those who had arrived after April 1616 and paid their own passage would receive fifty acres for themselves and an additional fifty for every person they transported. The latter arrangement, which became known as the headright system, was for the rest of the century the primary means by which laborers were recruited and sent to the colony”

– (Horn 2018: 138, emphasis added)

In this day and age, imagine someone paying for your airline flight from London to Richmond, Virginia only to have you work that debt off by doing chores around their house for the next 5-7 years!

It is not exactly an enticing strategy, is it? However, back in the early 1600s when the Virginia Colony was still underpopulated and land grabs in full swing, this was how the Virginia Company managed to establish its economic footing in the New World.

From the quote above, “shares” were issued by the Virginia Company to its shareholders for which the promise of large tracts of land enticed dreams of avarice for the potential wealthy adventurer in England. Some wealthy investors, who later became part of the established Virginia elite, would acquire thousands of acres at a time via this scheme!

An example in James Toone’s time would be none other than Moore Fauntleroy, who I’ve come across numerous times in researching our beloved James Toone of Virginia. Over the course of his illustrious career as an “ancient planter,” Moore acquired huge tracts of land along the Northern Neck of Virginia near to where our Tune family has its roots: (this is just a partial list and does not include his numerous sub-thousand acre grants!)

- 5,350 acres in 1650

- 5,054 acres in 1660

- Lands extending 25 miles in 1650

- 8,850 in 1650

- 2,600 in 1665

Although much has been written on the Virginia Company itself, I like New World, Inc by John Butman and Simon Target (cf. Sources section). It’s a robustly written account of the absolute insanity of the times and how the Virginia Company was eventually formed. Comparatively speaking, it was like trying to establish the first human settlement on the Moon or Mars!

Treatment of indentured servants ranged from violence and near total bondage to the mutually beneficial relationship of an apprentice who would eventually seek his own way in the world. To that end, terms of service were ideally to be no more than 7 years (5 being optimal) at which time the newly-freed man was supposed to be given some land, implements with which to conduct his own farm, and the all-important social connections which could inevitably bolster his chances of success in the ever-changing Virginia economy and socio-political landscape.

There are two truths here, as John McCusker (1991: 243-4) tells us: “The literature on the legal aspects of servitude is fairly complete, but we know much less about the actual functioning of master-servant relationships. We would also like to know more about what happened to servants ‘out of their time,’ an issue so far explored in detail only for the Chesapeake colonies in the seventeenth century.” However, Virginius Dabney refines the point a little bit more for us by allowing for the possibility of upward mobility “The indentures who were arriving in such large numbers were often persons of good standing in England, even ‘gentlemen.’ Some of them quickly worked their way up to positions of responsibility” (Dabney 1971: 34).

James Toone of Virginia was a headright in 1651. As a mark of his success, 12 years later James received headright lands of his own for the transportation of 4 people to Virginia from England in 1663! There is a distinct probability that he may have been associated with Moore Fauntleroy – both of these topics will be discussed in more detail as we proceed through this story of our Tune family! It is also interesting to note that headright land claims could be held and used years after they were granted.

Land Patent Explosion

Jamestown, Virginia is the the United States’ first permanent English settlement, founded in 1607. It predates the famous Plymouth Colony by 13 years. That being said, life in Jamestown in the 1610s and 1620s was not for the feint of heart! In fact, author James McDonald tells us: “The first permanent settlement in Virginia was begun as a bachelor kingdom, without the sound of the gentle voice of woman, and the cooing notes of infants” (McDonald 1907: 90).

It wasn’t until the early 1630s that females were expressly brought into the Virginia Colony to provide healthy breeding stock for the increasing male population whose heroic efforts were beginning to stick. They were becoming successful.

Life in the original Jamestown was rough and uncivilized up until the time the Virginia Company had been dissolved in 1624. As these formative decades passed, new English immigrants slowly moved up the coast from the James River creating the counties of Norfolk and Richmond and by the 1650s there was a push further north up into the Tidewater region as the Northern Neck exploded with land patents. By 1650 there were 60 patents granted along the Rappahannock totaling 53,000 acres; over the next two years 123,000 more acres were patented.

Fortunately, by the time James Toone arrived in Virginia in 1651 things had already changed for the better and life was heading towards an economic upswing. In 1634 there were only 7 counties in the Virginia Colony, comprised of large swathes of land which ran from the Tidewater region into the Fall Line. By 1651, the year James Toone arrived, there were now 10 counties, some of which had been subdivided. James settled in Northumberland County located in the Northern Neck region of Virginia.

After James had ended his indenture sometime around 1656 it is likely that he was amongst those families who had made the original push into the Farnham Creek area. During the 1660s and 1670s in the Farnham Creek basin and surrounding parishes we see an influx of families whose connections with one another are to become the bedrock upon which all of the descendants of James Toone of Virginia rest, the foundation of our Tune family genealogy and all of our future generations.

James Toone of Virginia and the Planter Class

According to current U.S. Census Bureau statistics, the population estimate for the State of Virginia as of 2013 was just over 8.26 million14; however, circa 1650 the population was a mere 15,000 people (CITE). As in England, the demographics of the Virginia Colony was very much class-based in the 17th and 18th century, consisting of Burgesses and wealthy land owners, merchants, yeoman, smaller land owners, as well as indentured servants. The Cavaliers fell into that small class of families that governed the colony, the rest into the majority of the population that constituted the economic base of the colony. Which side was James Toone of Virginia on?

James Toone of Virginia Establishes Himself

If James Toone arrived in Virginia in 1651, completed a hypothetically average indentured servitude of 5 years, that would mean that he was his own man by 1656. That would also mean that over the next 10 years: (1) he was given power of attorney in 1657 and 1659; (2) married his first *wife around 1658; (3) received a “deed of gift” in 1661; (4) facilitates a “land conversion” in 1663; (5) claims a John Tune as headright from England in 1663; (6) marries an Ann Duncombe about 1664; and, (7) had his first son (from Ann) William Tune born in 1667.

*We do know that James Toone had married previous to Ann Duncombe and had a son named “James Jr” who married a Mary Jackman in 1680. We also know that Ann Duncombe had been married prior to James Sr and then again after as James predeceased Ann in their marriage. It must also be stated that Ann’s surname Duncombe is, as of yet, unproven.

My WORKING HYPOTHESIS is that James Toone could not have married until 1656 or thereabouts. The source of my reasoning comes from David Hackett Fischer in his landmark publication “Albion’s Seed” where he reveals to us the fact that indentures were not allowed to get married during their period of service, by contract. If this fact holds true, and in fact James was an indentured servant, it then creates a clear picture of how James Toone would have moved within his social sphere given the early timeline of his life between 1651 and 1656.

There are TWO DISTINCT POSSIBILITIES regarding James’ life to which I’ve previously, and scantly, alluded and that is that: (1) James Toone was an indentured servant early on in his time in Virginia; or (2) James Toone was not an indentured servant. Each possibility allows for diametrically opposite life paths and functions of how we are to interpret the dates between 1651 and c.1656 in answering the question “what did James Toone do during this period of time?”

Early on in my research I followed the logic of: since James Toone was a headright, he therefore must have been an indentured servant. However, we know that generally speaking this was not always the case. There were may types of persons claimed as headrights, not all were indentured servants. Until I can prove he wasn’t, I am going to assume he was because this is what the research indicates and is the highest likelihood.

Again, restated, my working hypothesis is that James Toone was (or the probability is very high) an indentured servant based on the fact that no records of a James Toone (or other variation of this surname) have been found from his documented arrival in 1651 until he first appears on a legal document in 1657. This span of 6 years also coincidentally coincides with the average number of years an indenture would have served!

That being said, I will be allowing for both possibilities throughout the remainder of this article. Such is the nature of genealogy research over 370 years in the past! More on these questions and inklings as we continue to explore the life of James Toone of Virginia in this article!

Given the context of the times in England, as well as Colonial Virginia in the Tidewater region, James’ success was phenomenal. Or was it? I think it all comes down to who James Toone of Virginia was as an individual, on a personal level. If James was the type of person who had an egregious or undisciplined character, which was looked down upon in terms of ‘English’10 culture and accepted norms, he would not have made the connections that he obviously did in order to establish himself.

During the first four to five years of his life in the Chesapeake James must have worked for a family that would sustain his connections later on in life. During his indenture between 1651 and 165611 he proved himself to be an honorable laborer and a person of sound moral character; for in an age when death was rampant, secret marriages abounded, servants were commodities, and 20-30% of males died bachelors, James managed to encircle himself with a network of friends and families that would be the lifeblood of his existence.

The Billingtons, the Fauntleroys, the Williams, the Lawsons, the Powells, the Lewises, to name a few. One or any or all of these inter-related families must have been James’ benefactor(s) during his formative years in the Northern Neck region while he was in his 20s, single, and eager to establish his own line of descendants in this new land.

It is at this juncture that James Toone of Virginia and England becomes James TUNE.

STAY TUNED! OR TOONED! TO BE CONTINUED! This post will be updated and the story of James Toone of Virginia will continue as I continue to write. You can subscribe to this blog below to receive email updates.

– F+H+H (10 Apr 2022)

Acknowledgments

This biography of our ancestor James Toone could not, in any way, be possible without the support and research of Gloria Jeanne Tune whose tenacity in documentation and tireless effort in situating our family database online has been nothing short of Herculean. Gloria and I are 4th cousins, James Toone of Virginia is our 8th great grandfather.

Notes

1. There is ongoing debate on what exactly constitutes the Home Counties. From my personal knowledge, colloquially, this refers to the city of London, Kent, Middlesex, Surrey and Sussex. However, more formally it also includes Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Berkshire, and Essex.

2. 50% of the population increase of ALL of England ended up in London.

3. Presuming he was a younger sibling. Records from Rotherby might confirm him as a middle child.

4. “Most merchants trading with the Rappahannock were from the capital.” Horn 1994.

5. It is also possible that someone else, an investor, paid for the transportation costs and John King brokered the deal.

6. I have documented 16 different variations of the Tune surname.

7. Carlisle, Horn, and Fischer each briefly discuss terms of service.

8. Statistics for 1658 – 1705 in Maryland.

9. Cf. McCusker & Menard 1991 The Economy of British America p. 222-223.

10. Clearly, Colonial Virginia in James Toone’s time was an English settlement, governed by English law, English custom, and the adaptation of English culture to their new environment. It had not yet developed a distinctly ‘American’ identity.

11. Based on indenture estimates and averages. In point of fact we do not have any documentation of exactly how many years James Toone served, if he even was as an indentured servant at all.

12. The Interregnum from 1649 – 1660 had two distinct sub-parts: (1) The Commonwealth of England from 1649 – 1653; and (2) the Protectorate from 1653 – 1659.

13. He was subsequently reinstated by Charles II in 1660 and then removed by Charles II in 1677 after the events of Bacon’s Rebellion.

14. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/51.

Sources

- Adams, Stephen. 2001. The Best and Worst Country in the World: Perspectives on the early Virginia Landscape. Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press.

- Barratt, John. 2000. Cavaliers: The Royalist Army at War 1642 – 1646. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing.

- Bellany, Alaistair James and Thomas Cogswell. 2014. The Murder of King James I. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Bergreen, Laurence. 2021. In Search of a Kingdom: Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire. New York: Custom House.

- Beverley, Robert. 1855. The History of Virginia in Four Parts. Richmond: J. W. Randolph.

- Butman, John and Simon Targett. 2018. New World, Inc.: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers. London: Little, Brown & Co.

- Carlisle, Rodney P (ed.). 2010. Life in America: The colonial and revolutionary era. New York: Checkmark.

- Crowther, Prosser Jr. 2009. Rock Of Ages: The Story of 300 Years of Family Burials in Northumberland County, Virginia. VA: Northumberland Historical Press.

- Dabney, Virginius. 1971. Virginia: The New Dominion, A History from 1607 to the Present. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Davis, Virginia Lee Hutchinson. 2006. Jamestowne Ancestors: 1607-1699. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company.

- Elton, G. R. 1977. Reform and Reformation: England, 1509-1558. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Fischer, David Hackett. 1991. Albion’s Seed: Four British folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, David Hackett and James C. Kelly. 2000. Bound Away: Virginia and the Westward Movement. Charlottesville: UVA Press.

- Fetherston, John (ed.). 1870. The Visitation of the County of Leicester in the Year 1619: taken by William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms. London: Taylor and Co.

- Fraser, Antonia. 1974. Cromwell: The Lord Protector. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Gallay, Alan. 2019. Walter Ralegh: Architect of Empire. New York: Basic Books.

- Gies, Frances and Joseph. 1991. Life in a Medieval Village. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Genealogical Society of the Northern Neck of Virginia. 2012. The Shepherd’s Fold: Cemetery Records of Northumberland County Virginia Churches. VA: New Papyrus Publishing.

- Guppy, H. B. 1890. Homes of Family Names in Great Britain. London: Harrison and Sons.

- Hay, Douglas and Nicholas Rogers. 1997. Eighteenth-century English Society: Shuttles and Swords. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hibbert, Christopher. 1993. Cavaliers and Roundheads: The English Civil War, 1642 – 1649. New York: Schribner.

- Horn, James. 1994. Adapting to a New World: English Society in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake.

- Horn, James. 2006. A Land As God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America. New York: Basic Books.

- Horn, James. 2011. A Kingdom Strange: The Brief and Tragic History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke. New York: Basic Books.

- Horn, James. 2018. 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy. New York: Basic Books.

- Kelly, Brian C. 2003. Best Little Stories From Virginia. Naperville, IL: Cumberland House.

- Kennedy, D. E. 2000. The English Revolution, 1642-1649. London: Macmillan Press.

- McCartney, Martha W. 2012. Jamestown People To 1800: Landowners, Public Officials, Minorities, and Native Leaders. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company.

- McCartney, Martha M. 2007. Virginia Immigrants And Adventurers 1607-1635: A Biographical Dictionary Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company.

- McCusker, John J. 1978. Money And Exchange In Europe And America, 1600-1775: A Handbook. Chapel Hill: UNC Press.

- McCusker, John J. and Russel R. Menard 1991. The Economy of British America, 1607-1789. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- McDonald, James. 1907. Life in Old Virginia. Norfolk: The Old Virginia Publishing Company.

- Morgan, Edmund Sears. 1985. Virginians at Home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Nichols, John. 1815. The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicestershire, Vol. 1, Part 2. Digitised by the University of Southampton Library Digitisation Unit in 2010.

- Nugent, Nell. 1934. Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants, Vol. I-III. Richmond: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc.

- Ollard, Richard. 2000. The Image of the King: Charles I and Charles II. London: Phoenix Press.

- Price, Edward T. 1995. Dividing the Land: Early American beginnings of our private property mosaic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Purkiss, Diane. 2007. The English Civil War: Papists, Gentlewomen, Soldiers, and Witchfinders in the Birth of Modern Britain. New York: Basic Books.

- Valance, Edward. 2009. The Glorious Revolution: 1688, Britain’s Fight for Liberty. New York: Pegasus Books.

- Walsh, Lorena S. 2010. Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607 – 1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Wedgwood, Cicily Veronica. 1981. A Coffin for King Charles: The Trial and Execution of Charles I. Time-Life Books: Alexandria, VA.

- Wertenbaker, Thomas J. 1959. The Planters of Colonial Virginia. New York: Russell & Russell.

- Wolf, Thomas (ed.). 2011. Historic Sites in Virginia’s Northern Neck & Essex County. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Wrightson, Keith. 1995. English Society, 1580-1680. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

I am a descendant of James toone. My father, Roy white son of Benjamin buster white of tyronza Arkansas

Hi Stacy, thank you so much for finding this article! We have a massive Toone/Tune database on Ancestry and I’d love to connect with you on your line, please email me at fhf@familyhistoryfoundation.com if you are interested. My Toone line comes via Texas.

Hello. I had a Y-DNA test several years ago (since expanded to 111 markers). Although my surname is MALLETT I was surprised that I have four matches with men named TUNE descended from a James TOONE of Virginia 1625-1677 (and another named TOONE descended from a Robert TOONE of Belton 1520-1590). I do have a match with the surname MALLETT but the first four are less genetically distant than him (?!). I can only assume that we have a common male ancestor (and perhaps our surname was TOONE before it was MALLETT?!). This was a very interesting read and I look more to learning more about the TUNE/TOONE family.

I am a direct descendant of James.

I cannot remember dates but my research shows the family moved from Virginia to Tennessee. That’s where my grandfather was from.